It was close to lunch time on January 15 and Boston was experiencing some unseasonably warm weather as workers were loading freight-train cars within the large building. The United States Industrial Alcohol building was located on Commercial Street near North End Park in Boston. Listen to HISTORY This Week Podcast: The Great Boston Molasses Flood The molasses burst from a huge tank at the United States Industrial Alcohol Company building in the heart of the city. Interested more MIT-flavored history? Read a Slice post about The Technologist, a historical thriller that pits members of MIT's first graduating class against an evil genius setting off disasters in the Boston area in in 1868.Fiery hot molasses floods the streets of Boston on January 15, 1919, killing 21 people and injuring scores of others. He also was a founding member with Frederic Fay 1893 and Sturgis Thorndike 1895 of the engineering company Fay, Spofford & Thorndike, which now has offices in New York and New England. Spofford continued a distinguished career of teaching and research at MIT until retiring in 1940.

Ultimately the company paid the modern equivalent of several million dollars in out-of-court settlements. Spofford calculated, “A stress as great as 18,000 pounds per square inch is as high as should have been permitted under any circumstances.” However, the fatal load of 2.3 million gallons exerted pressure of 31,000 pounds per square inch on the tank walls, “a figure nearly double that which should have been allowed.” He noted, “The factor of safety is but 1.8, while ordinary practice would have called for from 3 to 4.”Īfter several years of hearings, a court-appointed auditor found USIA responsible. With its weak walls and shortage of rivets, he concluded, “In my judgment, the tank was improperly designed and its failure was due entirely to structural weakness.” In fact, during the initial explosion, witnesses described rivets shooting out everywhere like machine gun bullets. In addition, the tank lacked enough rivets to properly fasten the plates.

Spofford examined and tested pieces of the tank at MIT labs.Īccording to Dark Tide: The Great Boston Molasses Flood of 1919 by Stephen Puleo, Spofford reported that the steel plates were thinner than the original plans had called for and could not withstand the pressure of so much molasses. The company hired civil engineering professor Charles Spofford (Class of 1893), an authority on structural engineering and bridge design, to prove that USIA was at fault.

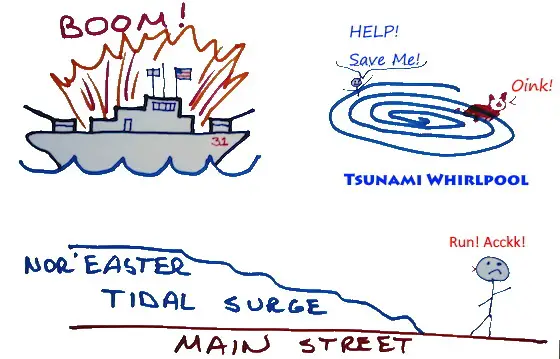

US Industrial Alcohol, the company owning the tank, steadfastly blamed anarchists.Īmong the litigants was the Boston Elevated train line, since the flood had severely damaged its overhead rail infrastructure in the North End. Three theories arose to explain the catastrophe: the tank exploded due to fermentation of the molasses anarchists or Bolsheviks set off a bomb, or a structural failure led to disaster. Litigation swiftly followed and lasted for years. Strong enough to knock houses off their foundations and sweep a train off its tracks, the wave killed 21 and injured 150 in the densely populated area. Flowing at the unexpected speed of 35 miles an hour, it formed a 15-foot high tsunami of 14,000 tons of viscous goop. On January 15, 1919, a 50-foot-high steel tank holding 2.3 million gallons of molasses suddenly ruptured in Boston’s North End. Almost a hundred years ago, Civil Engineering Department head Charles Spofford investigated and identified the cause of one of Boston’s most sensational disasters, the Great Molasses Flood. To determine causes and liability, many MIT professors and alumni have served as expert witnesses or on fact-finding commissions. Guest blogger: Debbie Levey, CEE technical writerĪccusations and emotions run high after sensational disasters.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)